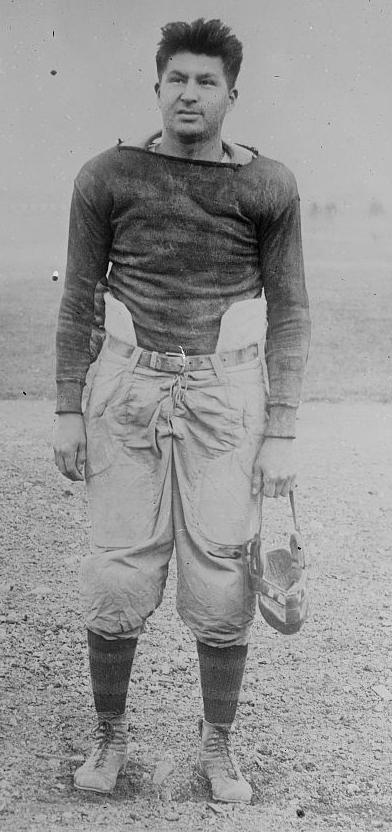

After commencement in the spring 0f 1914, Gus joined another football player, Fred Big Top (Piegan), in operating a horse rental business at Glacier National Park. At summers’ end, Lookaround returned to Carlisle but Joe Guyon didn’t. Just as the season started Gus wrote an article on the 60-piece Indian School band in which he played the helicon bass, a cousin of the sousaphone. In an attempt to shore up the backfield, Pop shifted Gus to fullback for the Lehigh game and quarterback against Dickinson College. A broken leg kept him out of several games but Warner put him in at center against Notre Dame.

After the season ended, Gus entered the Ford Motor Company intern program in Detroit, Michigan along with several teammates. They formed a basketball team in their free time. The fall of 1915 found Gus back at Carlisle playing football, making music with the band, and debating as a member of Invincible Debating Society. The Indian coaches, Victor “Choctaw” Kelley and Gus Welch, put him at left end this year. The dismal 3-6-2 season brought Gus’s football career at Carlisle to an end after having played every position except halfback at one time or another. With the spheroid left behind, he headed back to Detroit. He stayed on with Ford until September, 1916 when he returned to his home in Wisconsin.

It’s not clear what Gus did the next eleven months but the Carlisle school newspaper published on November 2, 1917 reported that he had enlisted in the army and was training at Camp Douglas, Wisconsin. Later that month he was reported as being “somewhere in France.” A month later he was on board the battleship U.S.S. New Hampshire. Wisconsin newspapers said he “is going to look around for German U-boats,” probably as a joke. In January, 1918 he visited Carlisle on his way to visit his family in Wisconsin. In February, he wrote that he enjoyed the Navy and “was soon to play in the championship football game of his ship’s league.” No mention was made about how he transferred from the Army to the Navy. The last mention of him in Carlisle publications came in March when he visited Wallace Denny at the school while his ship was in Philadelphia.

<end of part 2>