Assault on the Redskins and Lone Star Dietz

The Media Assault on the Redskins

For full disclosure, I must admit that, after the unlamented Steve Spurrier maligned the town and moved the Redskins’ summer camp out of Carlisle, I have much less positive feelings toward the team, its management, and ownership. About all I can say is that the Redskins didn’t advertise for Mosquito Magnet when they were in Carlisle and Carlisle’s gene pool is less diverse since they left.

The Washington Post has been advocating steadily for the Redskins to change their name for some time, with only the occasional nod to an appearance of objectivity. One of their writers even interviewed me about Lone Star Dietz last fall but included no mention of Ives Goddard’s research in his piece. Other newspapers have chimed in, with some no longer referring to the team by its name, but none with quite the fervor of The Boston Globe as demonstrated by their December 29, 2013 piece by Senior Staff Writer Kevin Paul Dupont (formerly with the Boston Herald American and The New York Times), “Redskins name controversy traces back to Boston.” While riddled with more errors and half truths than most other articles on the subject, this one contains all the usual arguments for the change. It also contains a provably untrue claim not previously posed but one that will likely be picked up by others. We’ll start with the old chestnuts first before addressing Dupont’s unique charge.

Redskins is derogatory

Activists, led by Suzanne Harjo, have filed lawsuits to force the team’s owner to change the name. Harjo claims the origin of the term “redskins” dates back to the onset of the French and Indian War during which she asserts the term derived from bounties paid for bloody Indian scalps. Team owners have prevailed in court so far but the activists continue their fight, surely encouraged by the strong media support. So successful have the activists been in convincing the media that the name is derogatory, most writers don’t consider other possibilities.

In 2005, Smithsonian Senior Linguist Ives Goddard conducted an exhaustive study of the origin of redskins, finding that the term was coined not by white men but by Illini. Both the term itself and the association of red to Indians’ skin color were benign references made by American Indians to differentiate themselves from white men and black men. Goddard found significant evidence to support his conclusions and none to support the supposed bloody scalp reference. Harjo provided no evidence to support her claim. Instead, she responded with an ad hominem attack, “I’m very familiar with white men who uphold the judicious speech of white men. Europeans were not using high-minded language. [To them] we were only human when it came to territory, land cessions and whose side you were on.”

Dictionaries first considered redskin to be derogatory in the 1960s, likely in response to the emergence of the bloody scalp origin. Prior to that, redskins was a neutral term. Internet searches for articles on the Redskins in the 1930s retrieved numerous articles about the Braves baseball team because local sports writers frequently used Redskins as a nickname for the baseball team during that time period.

The Annenberg Public Policy Center conducted a survey of American Indians in 2003-4 regarding the team name Redskins. Ninety percent didn’t find it offensive; nine percent did, and one percent had no answer. The Associated Press’s May 2013 poll of adults found seventy-nine percent in favor of keeping the name, eleven percent thinking it should be changed, eight percent weren’t sure, and two percent didn’t answer. In October 2013, President Obama interjected himself into the controversy when he said the team owner should “think about changing” the team’s name. The media drumbeat against the Redskins’ name and the President’s use of the bully pulpit have had little impact on the public’s perception of the issue as evidence by a January 2014 Public Policy Polling survey of registered voters which yielded strong support for the team’s name. When asked the question, “Do you think the Washington Redskins should change their nickname or not?” seventy-one percent said to not change the name, eighteen percent said to change it, and eleven percent weren’t sure. Three of the four WWII Navajo Code Talkers being honored for their service at the November 25, 2013 game wore Redskins jackets. When Roy Hawthorne, a leader of the group, was asked about the team’s name, He responded, “My opinion is that’s a name that not only the team should keep, but that’s a name that’s American.”

Further evidence of the public’s rejection of the media’s assault on the Redskins is illustrated by the turnout—617,767 total for 2013 regular season home games at FedEx Field. Fourth highest attendance out of thirty-two NFL teams doesn’t suggest that fans are repelled by their name. Washington, DC isn’t the only town with a Redskins football team. At least three high schools—Wellpinit HS, WA; Kingston HS, OK; and Red Mesa HS, AZ—proudly sport that name on their uniforms. One suspects that since all three schools have majority American Indian student bodies, they don’t use that name under duress.

George Preston Marshall was a racist

It’s widely accepted that George Preston Marshall was a racist, at least regarding black players. However, prejudice about blacks doesn’t always—and often doesn’t—translate into discrimination against other races, particularly American Indians. What isn’t widely known is that he had a lifelong fascination with Indians. This fascination predisposed him to name his team after Indians because he admired them. That he hired a head coach he thought was an Indian suggests that he held a positive view of Indians. Hiring four former Haskell players reinforces that point. A shrewd businessman like Marshall wouldn’t have selected a team name he thought ridiculed his players; it would’ve been bad for business. And business has been pretty good for the Redskins, making it one of the most valuable of all sports franchises.

Lone Star Dietz wasn’t an Indian

“Along with the change in coaching, the Boston professional football team has undergone another change, this time in name. Hereafter, the erstwhile Braves of pro football will be known as the Boston Redskins. The explanation is that the change was made to avoid confusion with the Braves baseball team and that the team is to be coached by an Indian, Lone Star Dietz, with several Indian players.” This announcement from The Boston Herald has the sound of having been taken from the team’s press release and likely originated from Marshall.

The activists and their media supporters constantly attempt to convince the public that George Preston Marshall never stated his intent to name the team in honor of his Indian coach and players, then claim that Lone Star Dietz had no Indian blood, all the while ignoring the four former Haskell Institute players mentioned in the announcement. That Dietz’s heritage is unclear makes their job easier because the issue of his parentage was at center stage during his 1919 trial for draft evasion. Keep in mind that even one of his strongest critics, Linda Waggoner, allows that he might have been part Indian although he wasn’t James One Star.

Dietz’s sensational draft evasion trial made headlines coast to coast. He claimed to be the long-lost nephew of Sioux warrior One Star who had befriended him at or around the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. It came out during his trial that the actual nephew, James One Star (who later called himself Jim Crazy Horse), was a decade older than Dietz and had attended and left Carlisle Indian School long before Dietz arrived there. Leanna Ginter Lewis, the woman who raised Dietz as her own, testified that her baby was stillborn and her then husband, William Wallace Deitz, disappeared into the Wisconsin woods with the dead baby and reappeared some days later with an Indian baby he purportedly fathered with an Indian woman during a separation in their tumultuous marriage. During the trial, she showed the court the red shawl in which the black-haired baby was wrapped. High school girls packed the Spokane, Washington courthouse to catch glimpses of Dietz, who had become quite a celebrity after winning the 1916 Rose Bowl and losing just two regular season games in his four years as a head coach. That he also acted in movies surely increased his celebrity status.

The jury hung at eight to acquit and four to convict. Charges were reduced to making inaccuracies in his draft registration and refiled immediately by the Deputy United States Attorney. Meanwhile, Dietz lost his money by investing in the Washington Motion Picture Company, which went bankrupt after Fool’s Gold, a movie in which he played a supporting role, failed to make enough money to keep the company afloat. By January 1920, he was broke and unable to bring the Mare Island Marine officers to Spokane to testify in his behalf, especially the Marine lawyers who advised him to fill out the registration form as a non-citizen Indian.

He then pled nolo contendre (meaning that he wasn’t admitting guilt but wasn’t fighting the charges any longer) to charges of falsifying his draft registration and was sentenced to thirty days in the Spokane County jail. That he was given a very light sentence during the hysteria after WWI in which people were receiving long sentences for merely criticizing the government wasn’t lost on the newspapers across the country. The Kansas City Star, for example, headlined its coverage “Easy on a Draft Dodger: Lone Star Dietz given only thirty days in jail.” Not explicitly stated was that he wasn’t serving his time in a federal facility, just in the local county jail. That the Deputy United States Attorney and judge probably agreed to this light sentence before he pled nolo contendre implies that they viewed his as a minor infraction, especially since the government was throwing the book at people accused of much less.

After Dietz’s biography came out, I found a Lone Star family listed on a census of Washburn County, Wisconsin, the county directly north of Barron County, the one in which Dietz grew up. The Lone Stars belonged to the Lost Tribe of the Chippewa (known today as the St. Croix Band of Lake Superior Chippewa). The easy proximity of the Lone Stars made William Wallace Deitz’s liaisons with a Chippewa woman plausible and the scraps of information he gave Lone Star and Leanna fit with what he told them. Lone Star was a romantic. To him the Sioux were noble warriors where the Chippewa were the familiar, commonplace Indians he lived around and played with as a child. Thus, he was predisposed to believe he was One Star’s nephew and may not have explored the possibility he was part Chippewa. The Marine officers’ testimony about training him was believable, because it’s easy to imagine him strutting around in a Marine officer’s uniform after football ended. Being so famous, the Marines would have likely assigned him to highly visible PR duties, something in which he would have excelled as he was an early motivational speaker.

Dupont made a number of aspersions against Dietz that are at best half truths. We address them them in order except for those related to cost which will be addresses in the section that follows:

“That coach, the flamboyant William ‘Lone Star’ Dietz, a man inclined to wear top hat and tails, years earlier was sentenced to 30 days in a California jail, exposed by the feds for pretending to be…an Indian.”

Dietz was flamboyant indeed but he was as likely to wear full Sioux regalia as he was top hat and tails, more so in later years. The 1916 Rose Bowl program features photographs of him dressed both ways. As discussed above, he served his sentence in the Spokane County, Washington jail, not in California.

“In the eyes of Uncle Sam, Lone Star Dietz, who indeed went on to recruit a number of native North Americans to play for the Boston Redskins, was nothing but an artful draft dodger. The government ultimately prevailed in its claim that he fabricated details of his Oglala Sioux heritage as a mean to avoid serving military duty in World War I.”

Dietz was a lot more to Uncle Sam than “an artful draft dodger” because, nine years after his highly publicized trial, Uncle Sam hired him to coach the government Indian school at Lawrence, Kansas, Haskell Institute (known as Haskell Indian Nations University today). It is difficult to imagine officials at Haskell and people in positions of authority elsewhere in the government being unaware of his trial. At Haskell he was treated as if they thought he was part Indian, something he never wavered from claiming the rest of his life. He was so successful in turning around the Fighting Indian football program they called him a “Miracle Man.” He never denied having Indian heritage, even when it was to his detriment as in his 1918 attempt to be named Notre Dame’s head football coach. He later shared with his players that Knute Rockne was chosen instead of him because he was too dark.

Dupont chose not to include the testimony of the Marine officers from Mare Island who trained him in military matters to enable him to enter officer candidate school after the football season ended. Not mentioned was that former players of his who were then serving in the Marine Corps at Mare Island recruited him to coach their football team and that Dietz could not serve as their coach if he just enlisted in the Marines; he wouldn’t be allowed to do that as an enlisted man. Also not mentioned was that Marine lawyers counseled him as how to fill out the registration form as a non-citizen Indian.

“It was the newborn’s death, she told the court, that prompted her husband to dash to the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, and return home with the infant who stood before the court that day as 35-year-old Lone Star Dietz. The account she gave was widely believed to have been scripted by her son.”

My recollection from reading the transcript of her testimony was that she gave no specific location where her husband got the baby. She just said something to the effect of “he disappeared into the woods and returned some days later.” Neither she nor Lone Star recalled much information as coming from William Wallace Deitz; he just shared a few phrases about the baby’s origin with them. Some in the courtroom surely believed or at least conjectured that Lone Star scripted Leanna’s account but a significant majority of the jury must not have thought that, considering they voted eight to four to acquit him.

“Upon arriving in Boston in 1933, seemingly no note was made of his prior incarceration.”

Dietz’s incarceration must have been a non-issue at the time; Marshall and the fans wanted a winning team and they were glad to have one of the best coaches leading the team.

Dupont wrote, “Dietz, the ex-jailbird who led Washington State to a Rose Bowl victory over Brown University his first year as a head coach, was hired in March 1933 as the new coach.”

According to Merriam-Webster, a jailbird is defined as: “a person who has often been in jail or prison; a person confined in jail; especially: a habitual prisoner.” Since Dietz was not in jail in 1933 and had only been in jail once—and only for 30 days—the definition of jailbird doesn’t apply to him. Whether Dietz was a jailbird or not has nothing to do with his being hired as coach of the Boston NFL team. Assassinating a person’s character is a strategy employed all too often these days when evidence is lacking to support a position. Dupont also damns Dietz with faint praise by downplaying the importance of the 1916 Rose Bowl game and omitting the number of honors Dietz has received for his coaching prowess, including induction into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2012.

“‘Football Braves Become Redskins,’ read the modest headline in the Globe on July 6, 1933. With zero fanfare, Marshall abruptly changed the team’s name. The brief non-byline story included no explanation by Marshall, only noting that he announced the move prior to departing (likely from Washington) for the league’s annual meeting in Chicago. The story otherwise reported the change to Redskins was in keeping with a plan that had Marshall and Dietz prepared to ‘sign up a number of Indian players’ and befitting a team that played its games in ‘The Wigwam.’”

Coverage in other newspapers added a little detail not found in The Globe article. The Herald provided the missing reason for the name change: “The explanation is that the change was made to avoid confusion with the Braves baseball team and that the team is to be coached by an Indian, Lone Star Dietz, with several Indian players.” The AP added a quote from Marshall: “So much confusion has been caused by our football team wearing the same name as the Boston National League baseball club that a change appeared to be absolutely necessary.” Whether confusion with the baseball team or dissatisfaction with or by Braves Field was the primary reason for the change is an open question because the move to Fenway Park wasn’t announced for two more weeks.

Redskins was the perfect choice for the team’s name. It minimized confusion for existing fans, related to Fenway Park’s baseball team, the Red Sox, while differentiating the teams from each other, and retained the nascent Indian motif. And the team had an Indian coach and four Indian players. What could have been better?

Cheap way out

The previous attacks on Marshall and Lone Star Dietz have been made in various ways by other critics but the one discussed in this section is original to Kevin Paul Dupont as suggested to him by Richard Johnson, longtime curator of the The Sports Museum located in Boston’s TD Garden.

“It appears the name change was nothing other than a cheap, pragmatic way for the Redskins to play under a new name at a new venue with uniforms that were but a year old.

…

“I suppose someone might find a smoking gun one day that proves otherwise, but by all looks of things, it’s 1933 and he has a trunk full of Braves uniforms from the first year, and now he’s at Fenway, and what’s he going to do? ‘I know,’ he says, ‘We’ll just call them the Redskins.’ Richard Johnson

…

“Marshall, by all accounts, was a real pain in the ass,” said Johnson. “His partners bailed on him after the first year, and he was asked to leave. It would make no sense to leave [Braves Field] of his own volition. It wouldn’t pay to move. They had a home, they had uniforms, a team name…and a team identity.

…

“Meanwhile, Snyder is left to answer today for the continued use of a team name born in Boston in the midst of the Great Depression. Even with better days promised with a new start in D.C., Marshall held on to the Redskins name, kept the uniforms and logo. He may not have liked his history in Boston, but he found it conveniently portable, and no doubt economical.”

There’s no doubt that George Preston Marshall was a successful businessman and little doubt that he pinched pennies wherever he could. For example, accounts exist of him demanding that fans return errant footballs that found their way into the seats. However, no evidence exists to support the supposition that Johnson made and Dupont spread without doing a bit of fact checking. To the contrary, considerable evidence exists that Marshall did not, in fact, continue to use the Braves uniforms after the team name changed.

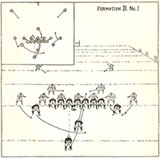

Newspaper coverage for the Redskins first home game announced, “Furthermore, they have a new coach, Lone Star Dietz; have new uniforms and some new players.” Grainy black and white period newspaper photos don’t show off the new uniforms very well, so football trading cards will have to suffice. Turk Edwards’ card shows the front pretty well where Cliff Battles gives a side view. The new colors are similar to those of Carlisle Indian School, which were red and old gold. A multi-color Indian head adorns the front of the jersey and stripes are placed at the wrists. (Carlisle’s stripes were just below the elbow.) Now that we know what the Redskins wore in 1933 and later, let’s find out what the Braves wore in 1932.

The Braves easily defeated the Quincy Trojans in a practice game at Fore River Field on September 18, 1932. The Braves didn’t look like a well-polished professional team. One reason was the long off-season lay-off. The other was sartorial. Because their new uniforms hadn’t arrived, they wore plain blue jerseys without numbers. Their dark blue jerseys with gold numerals arrived before their first home game. Although the black and white photos that accompany the article aren’t in color, they clearly show numerals on the front of the 1932 jerseys in the place where the Indian heads appear in 1933. This is further evidence, again easily found, that Marshall didn’t select Redskins for the team name as an economy move.

This uniform information brought to mind something that came up when researching Lone Star Dietz’s life. A Lafayette, Louisiana attorney I interviewed had represented the One Star family pro bono some years earlier in an attempt to receive compensation for the artwork Dietz made for the team in 1933. An irony is that, the attorney thinks, the family would have been pleased to receive some jackets and other Redskins memorabilia. The Redskins would have gained some Sioux fans without incurring legal fees. The statute of limitations had expired decades earlier so the family got nothing. Unable to find physical evidence that Dietz had designed the uniforms, such as sketches he made, I didn’t include the topic in the book. Now, I think it’s quite likely that Lone Star designed the 1933 Redskins uniforms. The team name changed months after he was hired. The Redskins’ new colors were similar to Carlisle’s. Dietz clearly had the artistic ability to design the Indian head for the jerseys. He had a long history of making art for teams and schools and participating in artistic endeavors seldom done by football coaches. And it wouldn’t have cost Marshall anything.

***

Washington, DC has some history with controversial sports team names. The Washington Bullets (formerly Baltimore Bullets) then owner, Abe Pollin, changed their name from Bullets to Wizards prior to the 1997-98 NBA season because the name contained violent overtones at a time when Washington, DC had a high crime rate. Some sixteen years later, Washington, DC still ranks near the top of the list of American cities with violent crime rates. Residents of our nations’ capital, on two separate occasions, rejected teams with a name so disreputable, merely renaming the teams wouldn’t have been enough to convince fans to fill the seats for their games. Both the teams had to move to the middle of the country to remove the stench of the loathsome name both teams wore—the Senators. Washingtonians have not rejected the Redskins as they did both Senators teams, they have embraced them.

1932 Boston Braves new uniforms—dark blue with gold numerals

1933 Redskins uniform design

Page from 1916 Rose Bowl program includes two photos of Dietz instead of one picture of each head coach.

Some examples of Lone Star Dietz’s artwork:

Leave a comment