Andre Billeaudeaux, historian and co-founder of Native American Guardians Association (NAGA), thinks opponents of the Redskins name don’t know what they’re talking about. “These people are just ignorant. It’s toxic ignorance. It’s group think. It’s the psychology of a group that has no idea what they’re doing, but they won’t listen to us [NAGA], either.”

The origin of the Redskins name and logos go back to 1912 when James Gaffney, of New York’s Tammany Hall, purchased the Boston Rustlers National League baseball team. He renamed the team as the Braves and used an image inspired by Saint Tammany for the team’s logo. That image is prominent on the left sleeve of Babe Ruth in a photo taken in 1935.

When a group including Washington laundry magnate George Preston Marshall purchased an idle NFL franchise and established a team in Boston, they named the team the Braves. It was common for upstart NFL teams to name themselves after established baseball teams, particularly when they shared the same field. The new Braves’ uniforms didn’t include an Indian motif. Instead they wore jerseys of a simple design in Marshall’s company’s colors: blue and gold.

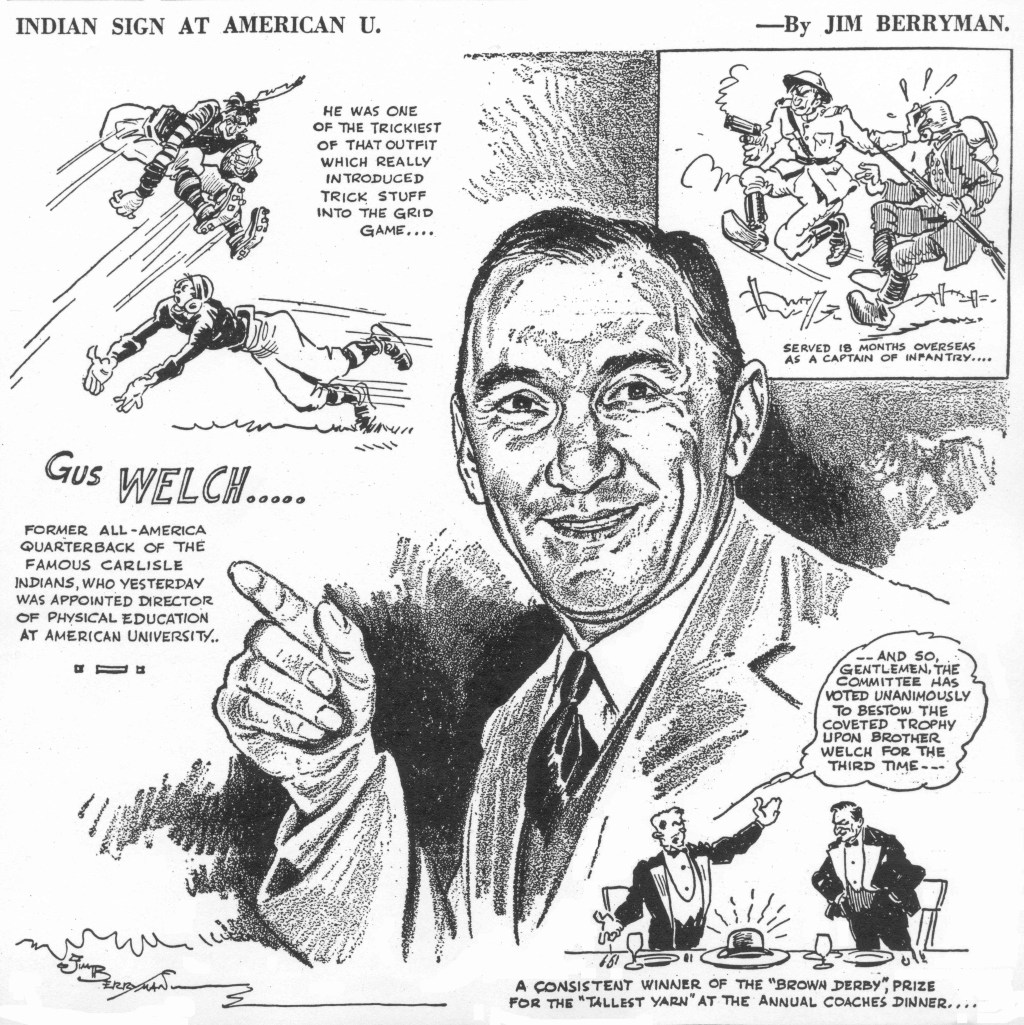

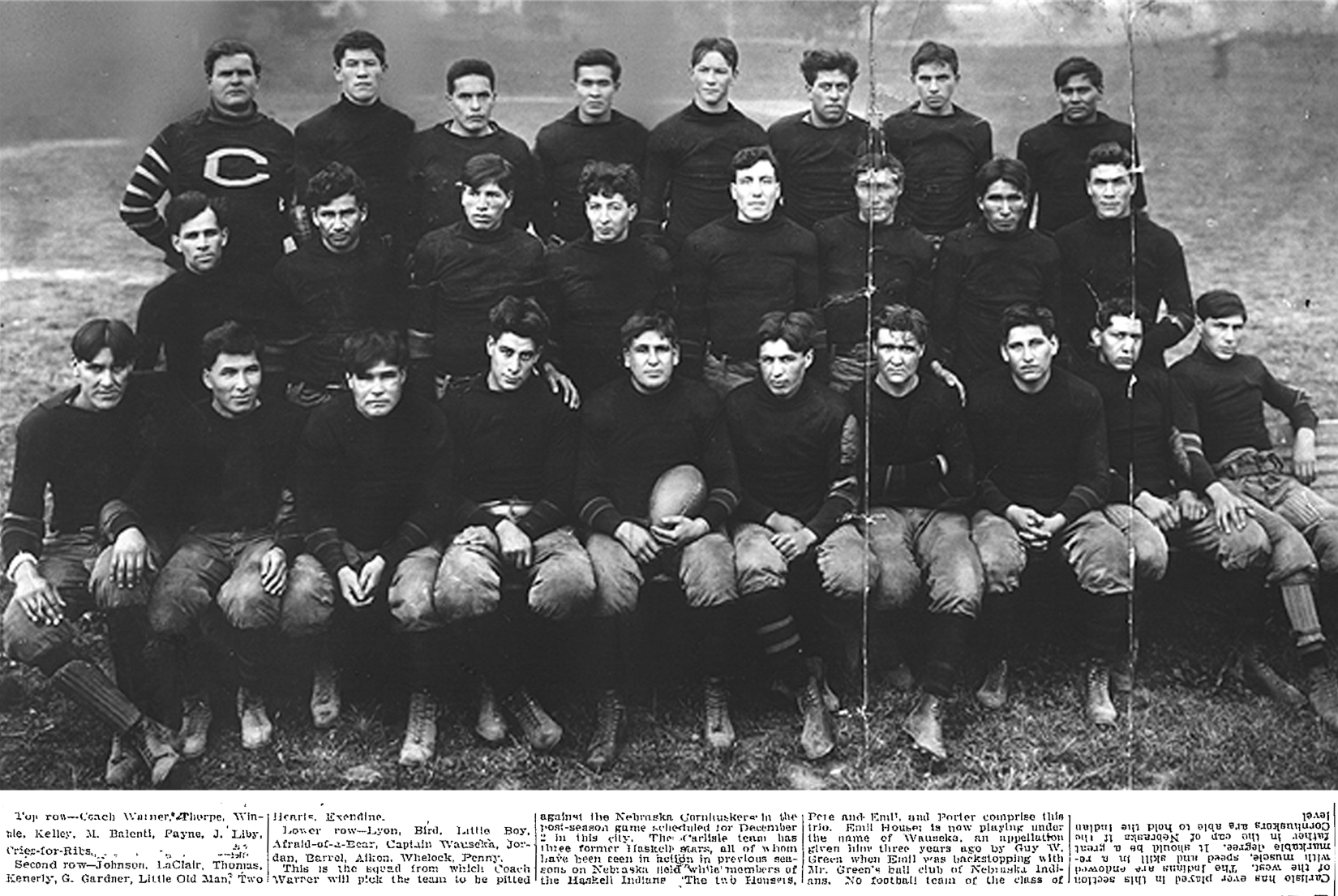

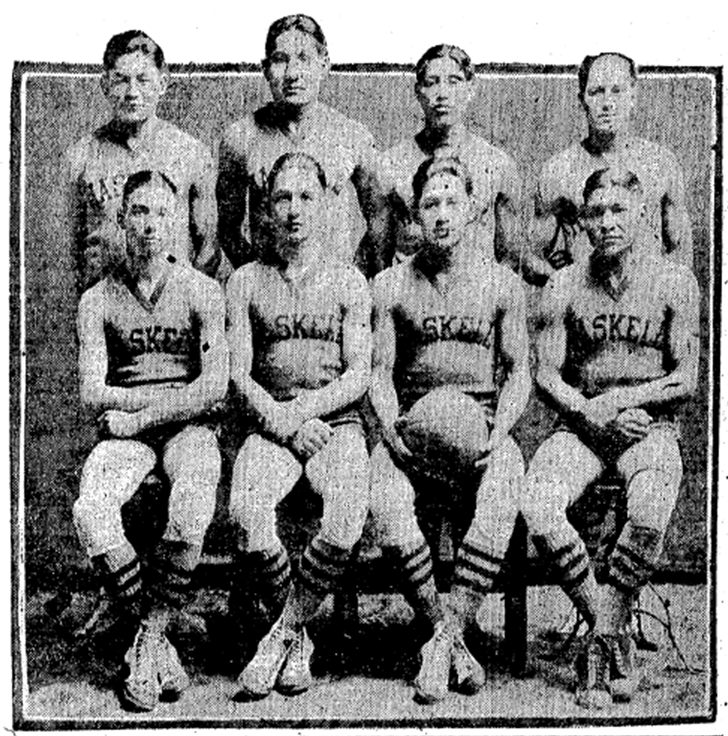

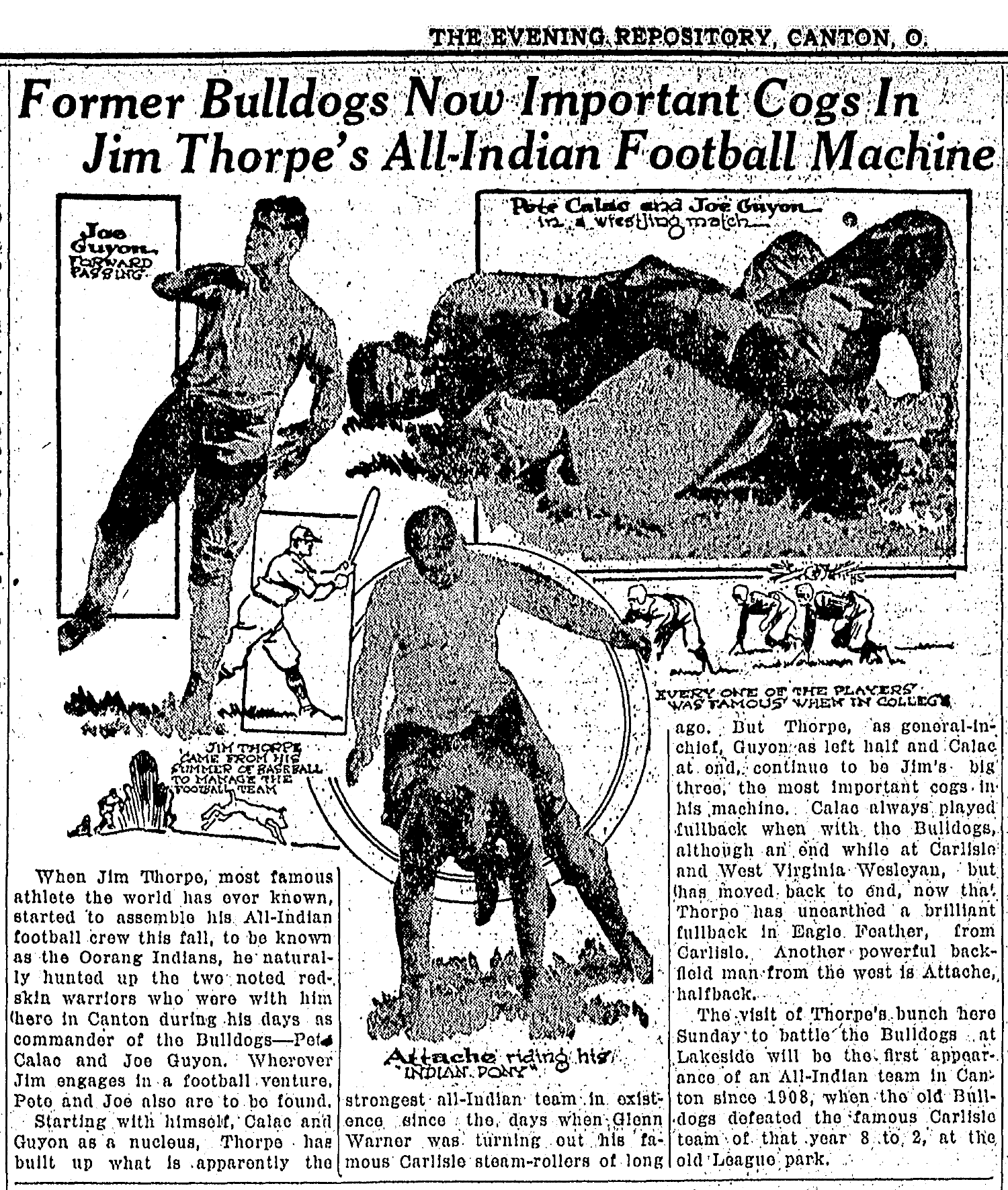

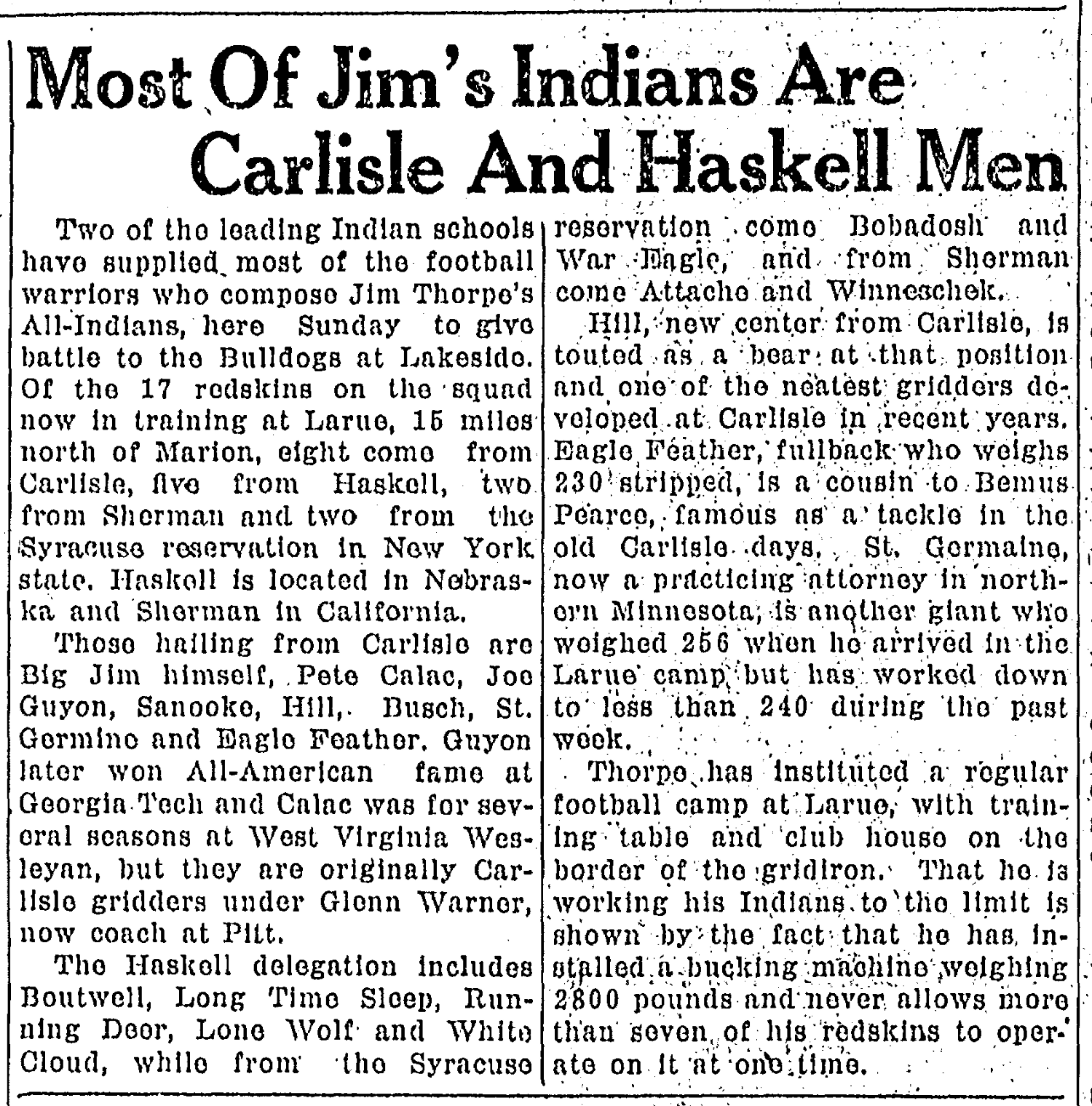

As a .500 first season, Marshall’s cohorts left, leaving him as sole owner of the team. He fired the coach, Lud Wray, and hired Lone Star Dietz, a Carlisle Indian School alum who had had success coaching at the college level. Dietz brought four of his Haskell Institute (today’s Haskell Indian Nations University) Fighting Indians star with him. The figure on the Braves’ letterhead and pin is different than the one used by the baseball team. On the baseball team logo, the man wore a headdress where the football logo image only had three feathers. I’m not qualified to determine if the football team used Saint Tammany’s profile or not. Having red on the letterhead suggests that the team’s colors changed shortly after Dietz became their head coach. The existence of the pin argues against Dietz changing the logo because he was only with the team a short amount of time before the team name was changed and it was during the off season. So, the logo on the button was probably created for the 1932 season.

One question never asked is: Why did Marshall change the team’s colors? A 1933 jersey shown below has red as the primary color and is trimmed with gold and black bands. These colors are similar to Carlisle’s colors and the stripes on the cuffs are reminiscent of the below-the-elbow stripes on the Indians’ jerseys. Some have attributed the design of the Redskins’ logo to Lone Star Dietz. The image may have preceded him; it’s not clear when the team adopted it. Dietz likely borrowed the concept from the NHL Blackhawks’ design and placed the logo on the front of the jersey.

Probably to save money, Marshall moved the team from Braves Field to Fenway Park. To eliminate confusion with the baseball team, he felt he had to change the name. Some think red was chosen because they were then based on the Red Sox home field. A Boston newspaper writer claimed that Marshall chose the name to save money by not having to buy new uniforms. As shown in this piece, both colors and design of the team’s uniforms changed when the team’s name changed. However, the team had to wear the old uniforms in the first game of the 1933 season because the new ones hadn’t arrived yet.

Billeaudeaux thinks otherwise. “Redskins is not about race. It’s a warrior who’s gone through the bloodroot ceremony. “They shave their heads and surrender their souls to their Creator. They paint themselves red as if they were born new into the world.”

“The Redskins were the only minority representation in the entire NFL and it was a real person, not a mascot,” said Billeaudeaux. “The name Redskins is a national treasure and for that reason it should be protected. It’s a cultural treasure and deserves to be protected and understood. It’s not just about the football team. It’s about the DNA of the nation.”

NAGA members aren’t the only people who prefer Redskins for the team name. As of this writing, 130,790 people had signed NAGA’s petition demanding the team name be changed back to Redskins. “Redskins Fans Forever,” a Facebook group with 61,600 members, refers to the team only by its historic name.

Ninety percent of Native Americans around the country supported the Redskins name in a Washington Post poll in 2016, as the woke assault on the traditional name grew stronger.

Red Mesa High School on a Navajo reservation in Arizona recently installed a new football field with the Washington Redskins logo on the 50-yard line.