Jim Thorpe’s return to Carlisle after the 1912 Olympics was incorrectly described in at least one newspaper of the day and that description has found its way into current books on Jim Thorpe. Fortunately, The Star-Independent of Harrisburg, PA captured the event in minute detail in its August 16, 1912 edition. However, the article was too detailed to be included in this short piece. There is only room to summarize it here.

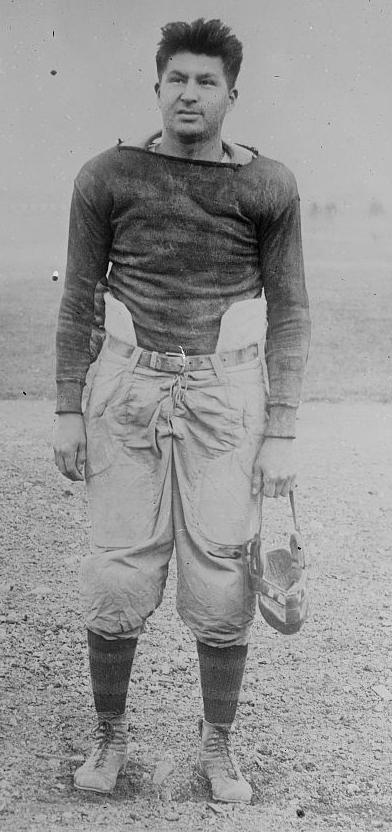

A crowd estimated to be between six and seven thousand people congregated at the Cumberland Valley Railroad (CVRR) station across from the James Wilson Hotel a block from the square in Carlisle for Thorpe’s expected arrival at 12:30 p.m.. The crowd-shy hero avoided this multitude by getting off the train at Gettysburg Junction, where the South Mountain Railroad connected with the CVRR, about a mile east of the square. Automobiles waiting there secreted Thorpe, Lewis Tewanima, and Pop Warner to Carlisle Indian School, where they were “greeted informally by students and their closest friends.”

From the Indian school the trio progressed to the parade which was split into three divisions, each of which was formed separately. The honorees were part of the first division which assembled along North Hanover Street, with its head at High Street (colloquially Main Street). Scheduled to start at 2:00 p.m., the parade, led by the first division, progressed east on High Street to Bedford Street, then followed a circuitous route along portions of each of the major streets in the center of town, eventually arriving at Biddle Field on the Dickinson College campus. There the official festivities started. After much speechifying, various events took place in town and on the Indian school campus (Carlisle Barracks). Fireworks were scheduled for 8:30 p.m. (EST probably), which were followed by an invitation-only reception and dance in the school’s gymnasium (present day Thorpe Hall) to close the day’s festivities.