Last time, Asa Sweetcorn explained his strategy for getting more attention from sportswriters to Gus Welch. As it turns out, the wily Indian continued to fool sportswriters long after his death. Welch described his former teammate: “This Sweetcorn was a very rugged Indian, although he only weighed about 160 pounds and probably nowadays [1933] would just be turned over to the intramural department.”

On page 258 of The Real All Americans, Sally Jenkins describes Sweetcorn: “He was an enormous, brawling, swilling man who wore size twenty-one collars and was able to ram his head through a wooden door in a liquored-up stupor.” Welch definitely didn’t describe Sweetcorn as being enormous. To the contrary, at about 160 pounds he was far from large as a football player in his day. Two decades later, he would not be given a chance to make the varsity in Welch’s opinion.

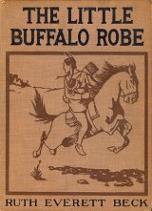

A photo of Sweetcorn in his Carlisle Indian School football uniform supports Welch’s description. He appears to be no larger than average size and without a thick neck. If Asa ballooned up to the size Jenkins described, it must have been after he left Carlisle.

The condition of Sweetcorn’s jersey in the photo supports Welch’s assertion that he received quite a beating in some games. Why he was wearing that particular jersey is unknown. What is known is that new jerseys were in limited supply. Each year, the varsity players got new jerseys and handed their old ones down to the second team who handed them down to the third team or the junior varsity who in turn handed their old ones down to the shop teams. It’s likely that his old jersey was in better shape than this one, but he may have worn this one as a badge of honor to reflect his toughness.