Archive for the ‘Carlisle Indian School’ Category

June 5, 2012

While browsing through Two Hundred Years in Cumberland County for something unrelated to Carlisle Indian School, I stumbled across a short article that, although moderately interesting in itself, brought an entirely different article to mind. In 2008, I wrote about an article written by a James C. McGowan that is loaded with falsehoods. Honest errors are one thing but some of these seem to be made up from whole cloth. To make matters worse, this false information has been disseminated from WorldAndI.com, a paid “educational” web site that flogs subscriptions for schools, districts and individuals, since 2007.

The article that caught my attention today was titled, “Autoists Arrested.” In July, 1906, G. Wilson Swartz, Esq. and Albert E. Caufman were brought before Burgess Brindle for breaking Carlisle Borough’s five-mile-per-hour speed limit. None of the police officers who observed the drivers would testify that Swartz “goes faster than some of the drivers of the big machines….” This is further evidence to show that McGowan’s claims about Warner being the “first man in town to own an automobile” is patently false. One wonders about McGowan’s motives for promulgating such unfounded claims. Accuracy is something about which McGowan and, by extension, WorldAndI.com have little concern.

McGowan wrote the following in a section of the article that attacked Pop Warner:

As the Redmen beat one top team after another, including Pitt, Navy, Yale, Syracuse, and Rutgers, the Athletic Fund swelled with cash. Pop Warner took to wearing diamond jewelry, and he became the first man in town to own an automobile.

Anyone the least bit familiar with Carlisle Indian School football knows that the Indians never beat Yale. Even those who are familiar would be hard pressed to name a year in which Carlisle beat Rutgers because there is no record of the two teams playing each other. Warner wasn’t living in Carlisle in 1906 and didn’t return to live there until 1907, at which time he had an automobile. Little is known about that car but Warner was known for buying inexpensive old clunkers and tinkering with them until he got them running. Regardless, this piece further demonstrates that other Carlislians had autos well before Pop Warner.

http://www.worldandi.com/subscribers/feature_detail.asp?num=25821

Tags:1906 speeding ticket, Albert E. Caufman, Burgesss Brindle, First automobile, G. Wilson Swartz, James C. McGowan, WorldandI.com

Posted in Carlisle Indian School, Pop Warner | Leave a Comment »

May 29, 2012

Thursday evening, I had the pleasure of attending the kick off reception at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, DC for their new exhibit, “Best in the World: Native Athletes in the Olympics.” This special exhibit, which runs through September 3, is timed to honor the 100th anniversary of the performance of two Carlisle Indians in the 1912 Stockholm Games but doesn’t limit itself to just their performances. In fact, the first thing one sees upon entering the exhibit is a blown-up photograph of Frank Mt. Pleasant broad jumping while wearing his Dickinson College jersey. He competed in the 1908 games in London. The exhibit also includes a photo of Frank Pierce, younger brother of Carlisle football stars Bemus and Hawley, competing in the marathon in the 1904 Games held in conjunction with the St. Louis World’s Fair. He is believed to have been the first Native American to compete for the United States in the Olympics. Enough about the exhibit, you can see that for yourself.

At the beginning of the reception, the dignities present were introduced. There is no mistaking Bill Thorpe due to his strong resemblance to his father. Bill is lending the use of his father’s Olympic medals to the NMAI for this event. Lewis Tewanima’s grandson was also present. He took the time to explain the importance of the kiva to Hopi culture. It was quite enlightening. Billy Mills, who broke Lewis Tewanima’s record for the 10,000 meters and won the gold medal in the 1964 Olympics spoke and was taped by a cameraman as he walked from exhibit to exhibit.

Some writers were also in attendance. Robert W. Wheeler, who wrote the definitive biography of Jim Thorpe, and his wife, Florence Ridlon, whose discovery of the 1912 Olympics Rule Book behind a Library of Congress stack made the restoration of Thorpe’s medals possible, was also present as was Kate Buford, the author of a recent Thorpe book. The apple didn’t fall far from the Wheeler-Ridlon tree as their son, Rob, whose website, http://www.jimthorperestinpeace.com, supports the effort to have Jim Thorpe’s remains relocated to Oklahoma.

More about the exhibit can be found at http://nmai.si.edu/explore/exhibitions/item/504/

Tags:10000 meters, 1912 Olympics, Best in the World, Billy Mills, Bob Wheeler, Flo Ridlon, Frank Pierce, Kate Buford, Lewis Tewanima, marathon, Rob Wheeler, Stockholm

Posted in Bemus Pierce, Carlisle Indian School, Frank Mt. Pleasant, Hawley Pierce, Jim Thorpe | Leave a Comment »

May 24, 2012

Tonight, the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, DC holds a reception to kick off its new exhibit, “Best in the World: Native Athletes in the Olympics,” to celebrate the athletic achievements of Native Americans on the 100th anniversary of the 1912 Stockholm Games that featured legendary performances by Jim Thorpe and Lewis Tewanima. I am attending because Bob Wheeler, Jim Thorpe’s Boswell, is to speak there. While making preparations for attending this event, I received some unexpected news.

The National Football Foundation (NFF) released its selections for induction in the College Football Hall of Fame Class of 2012 and Lone Star Dietz was finally on the list. As blog followers probably know, Greg and John Witter, first cousins and rabid Washington State football fans, and I campaigned to get Dietz placed on the Hall of Fame ballot some years ago. Getting his won-loss record corrected was the key to getting him nominated but there were larger obstacles yet to come.

Lone Star Dietz died in 1964 and there are few people still alive that knew him. Also, he coached at schools with smaller alumni bases and less clout than the major football factories. Washington State, for example, couldn’t muster the support for him that, say, Ohio State could for John Cooper or Michigan could for Lloyd Carr. While both these recent coaches had very good careers, neither had the impact on the history of the game as did Dietz. It’s one thing to inherit a strong program and be a good steward, but it is quite another to rebuild a floundering program from the ground up, something that Lone Star did multiple times.

The closest he came was in 2006 when the selectors chose Bobby Bowden and Joe Paterno instead of the people who were on the ballot. A couple of years ago, when Lone Star’s name was dropped from the ballot, I gave up all hope of him ever being selected. I didn’t even know that his name was on the Divisional ballot this year, so was shocked when I started receiving phone calls from reporters on Tuesday afternoon.

All I can say is that it’s long overdue. Although he’s being brought in through the back door, so to speak, he will finally be in. He’s the first Carlisle Indian to be inducted as a coach; the rest were as players. Whether this honor is enough to offset the many indignities Dietz suffered and mollify the Lone Star Curse is yet to be seen.

http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/cougarfootball/2018262997_dietz23.html

http://www.spokesman.com/stories/2012/may/23/blanchette-wsu-legend-dietz-gets-his-due/

Tags:1912 Olympica, Bobby Bowden, College Football Hall of Fame, Greg Witter, Joe Paterno, John Witter, Lewis Tewanima, Lone Star Curse, National Football Foundation, National Museum of the American Indian

Posted in Carlisle Indian School, Doctors, Lawyers, Indian Chiefs, Football, Jim Thorpe, Lone Star Dietz, Washington Redskins, Washington State University | Leave a Comment »

May 17, 2012

Jim Thorpe won the 1500 meter run, the last event of the pentathlon, with a time of 4 minutes 44.8 seconds. Avery Brundage did not finish but was awarded seven points, comparable to a last place finish. Whether he started and did not finish or just didn’t bother to run at all is unclear. Ironically, Thorpe could have finished dead last in the 1500 meters and still won the pentathlon but he probably never considered loafing to save his energy for the decathlon. Brundage finished in sixth place overall, ahead of Hugo Wieslander, who finished fourth in the 1500 meters. The best Brundage could hope for if he came in first, second or third was a bronze medal because, even if he finished dead last, Ferdinand Bie of Norway would have had only 22 points overall as he had only 15 points coming into the 1500 meters where Brundage already had 24. A first place finish would have given Brundage 25. A fourth place finish would have given him 28 points, still good enough for a bronze because James Donahue and Frank Lukeman both finished with 29 points in a tie for third place. The tie was broken by recalculating their results using the method used for the decathlon with the result that Donahue was awarded the bronze medal

According to Wikipedia, Brundage chose not to compete in the final event of the decathlon, again the 1500 meter run, and later regretted the decision. It may be that he also chose not to run the 1500 meters in the pentathlon as well. Perhaps his biographer, Allen Guttman, can shed some light on this but it has been decades since he wrote about Brundage and he may have forgotten the details.

Something that is clearer now is that the Brundage who came in second to Frank Cayou in a track meet held at the University of Illinois on April 28, 1900 probably was Avery. Although still in high school in Chicago, his times were already good enough to compete with college boys.

Tags:1500 meters, 1912 Olympics, Allan Guttmann, Avery Brundage, Ferdinand Bie, Frank Lukeman, Hugo Wieslander, James Donahue, Pentathlon, Stockholm Olympics

Posted in Carlisle Indian School, Frank Cayou, Jim Thorpe | 1 Comment »

May 15, 2012

Six days before beginning the decathlon competition, Jim Thorpe won the Men’s Pentathlon (not to be confused with the Modern Pentathlon which will be discussed later). Unlike the decathlon, all five pentathlon events were held on the same day, July 7, 1912. The first event was the long jump which Jim Thorpe won with a jump of 7.07 meters. Average Brundage’s 6.83 meter jump was good enough for fourth place. Next up was the javelin which was won by Hugo Wieslander of Sweden with a throw of 49.56 meters. Thorpe’s 46.71 was good enough for third place while Brundage’s 42.85 was ninth. The third event was the 200-meter run which Thorpe won with a time of 22.9 seconds. Brundage came in 15th.

After three events were completed, only the top twelve were allowed to continue; the rest were eliminated. It isn’t clear to me if the rules called for only the top twelve to continue or if those with composite scores higher than 25 were eliminated. Either scheme arrives at the same place in this case. Jim Thorpe was the overall leaders at this point with two firsts and a third place finish for five points total (1+3+1). Avery Brundage’s 22 points (4+7+11) kept him in the game tied for seventh place.

Only the top six competitors were allowed to continue after the fourth event, the discus. Jim Thorpe won that one too with a throw of 35.57 meters. The discus throw must have been Avery Brundage’s best event because he placed second in it. When overall scores were recalculated to determine who made the cut, Thorpe was, of course, well ahead in first place at six points. Surprisingly, Brundage was tied for third with 22 points. Because two men tied for sixth place, seven were allowed to compete in the last event.

<continued next time>

Tags:1912 Olympics, Avery Brundage, Hugo Wieslander, Pentathlon, Stockholm Olympics

Posted in Carlisle Indian School, Jim Thorpe | Leave a Comment »

May 10, 2012

This year is the 100th anniversary of the 1912 Olympic Games that were held in Stockholm, Sweden. What makes that important to us is the participation of two Carlisle Indians: Jim Thorpe and Lewis Tewanima. Writers across the country and even from England are working on articles about these games and the two men who starred in those games. The National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, DC is even opening an exhibit concerning American Indians’ participation in the Olympics on May 24. As a result, experts such as Bob Wheeler are being interviewed by various reporters and other writers. Even I am being asked to verify details.

The other day, I got a phone call from someone about a detail about which I had never given any thought: exactly when was the decathlon competed in the 1912 Olympics? Fortunately, with the use of the Internet, the answer could readily be found. The 1912 Decathlon was competed over three days. On the first day, July 13, the 100 meters, long jump, and shot put were held. The second day, July 14, hosted four events: 400 meters, high jump, discus throw, and 110 meter hurdles. On the third day, July 15, were the pole vault, javelin throw, and 1,500 meters.

Something that I find interesting is that Jim Thorpe tied for third in the pole vault, an event for which his physique was not well suited. Pole vaulters tend to be wiry, something that Thorpe wasn’t. Yes, he had tremendous upper body strength, but that was offset by his overall body mass as muscle is heavy. His great leg strength and running speed probably made up for his weight as he cleared 3.25 meters (10 feet 7.95 inches) in those pre-fiberglass pole days.

The decathlon was a battle of endurance as much as anything. Of the 29 athletes who started the event on the first day, only 12 finished all 10 events. Among the non-finishers was Avery Brundage. After finishing 10th in the pole vault, Brundage dropped out without competing in the javelin or 1,500 meters. Even at that, he is listed as placing 16th in the decathlon.

Tags:1912 Olympics, Avery Brundage, decathlon, Lewis Tewanima, Stockholm

Posted in Carlisle Indian School, Jim Thorpe | Leave a Comment »

May 8, 2012

Vance McCormick wasn’t a slacker child who lived with his wealthy parents and coached the Carlisle Indian School football team to give himself something to do, he worked in the family businesses. After he returned home from Yale in 1893, he helped his father operate his many businesses that included Central iron and Steel, Dauphin Deposit Bank, and Harrisburg Bridge Company. After his father died in 1897, Vance was in charge of the entire enterprise. The McCormicks were hard working Scots-Irish Presbyterians who attended Pine Street Presbyterian Church. At Yale, Vance split with his father on politics and became a Democrat.

In 1900 at age 27, Vance began his career in politics by running for and winning a seat on Harrisburg’s common council from the 4th ward. About the time he turned 30, he began a term as mayor of Harrisburg. McCormick’s legacy to Harrisburg is still seen today in the city’s park system. Less visible, but more impactful, are the water filtration plant that supplied clean drinking water to the residents of Harrisburg at a time when neither Philadelphia nor Boston had such a facility. He also had 45 miles of city streets paved. A reformer, Horace McFarland credited him with cleaning up Harrisburg morally as well as physically as fast as he could in his one term as mayor. And he wasn’t a full-time mayor! In 1902, he also became publisher of the Patriot-News, which he had ferreting out Republican corruption. He ran unsuccessfully for Governor in 1914 as organized labor and liquor interests opposed him. Today, he is perhaps remembered most for what he did on the national level.

McCormick’s restructuring of the moribund state Democratic party was a turning point in his political career. He was instrumental in shifting the Democrats to progressivism. Vance became a major player on the national stage. He was chairman of the Democratic National Committee (1916-19) and served as Woodrow Wilson’s campaign manager. He chaired the War Trade Board (1916-19) and served on the Commission to Negotiate Peace at Versailles in 1919.

After the war, McCormick returned to Harrisburg where he published both the Patriot-News and the Evening News. At age 52, he married for the first time to the widow of eight-term Republican congressman Marlin Olmsted. He died in 1946 at his country home, Cedar Cliff Farms, across the Susquehanna River from Harrisburg.

Tags:Cedar Cliff Farms, Evening News, Horace McFarland, Marlin Olmstead, Patriot-News, Treaty of Versailles, Vance McCormick, War Trade Board, Woodrow Wilson

Posted in Carlisle Indian School, Football | 2 Comments »

May 3, 2012

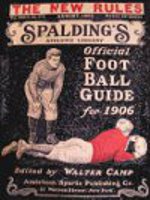

We need a little more information on Carlisle’s first coach to put the man in proper perspective. Vance McCormick was a great player, but was he a good coach? We already know he was a Walter Camp All America quarterback at Yale in 1891. Looking closer at the caption under his photo in the 1892 Spalding’s Guide reveals that he was also captain of the 1892 Yale squad. In those days being captain meant a lot more than it does today. Captains took a leadership role unknown to today’s players. They were field generals who directed their teammates’ actions when they were on the field of play. Coaches weren’t allowed to send in instructions—even via substitutions. So, a former Yale captain would have been better prepared than an ordinary player to coach a team. But this was no ordinary team. In the beginning, Carlisle Indian School football players had no previous training in the sport. Many had likely played on shop teams but those teams wouldn’t have had coaches (or at least coaches who knew anything about football) and the players would not have been taught the fundamentals of the game.

Vance McCormick probably the extent of the challenge when he took on the job. His teammates at Yale had likely been coached prior to college at the high schools or prep schools they attended and knew the fundamentals before arriving in New Haven. Moreover, they weren’t going to be on the varsity team the first year there anyway. That year would be spent on the freshman team, where they would work on the fundamentals extensively. Given McCormick’s family background, it is likely that he was well coached before arriving in New Haven. Vance McCormick wasn’t born with a silver spoon in his mouth—a whole tea set is more like it. Before coming to Yale, McCormick was educated at Harrisburg Academy and Phillips Andover, private schools that likely had coaches for their football teams.

So, Vance McCormick was probably better suited to coach a team than were his former teammates, but was likely unprepared to coach players who didn’t know the fundamentals or had little prior exposure to the English language. In spite of that, he recognized that the players were athletically gifted and got them started on the road to eventual fame on the gridiron.

Tags:1892 Yale, Harrisburg Academy, Phillips Andover, Vance McCormick

Posted in Carlisle Indian School, Football | Leave a Comment »

May 1, 2012

While cleaning up the scanned files in preparation of reprinting the 1892 Spalding’s Guide, I noticed a photograph of Vance McCormick on the page opposite page 17. Walter Camp had named the Yale star as the quarterback of his 1891 All-America team, an honor that earned his photo a page in the next year’s Spalding’s Guide. A friend, Nancy Luckenbaugh, taught at Carlisle Indian School and, in 1894, invited him to make the trip from his family’s home in Harrisburg to look over the football material that could be found there. McCormick had graduated from Yale in 1893 and was living at home and working in the family businesses at that time. Liking what he saw, he agreed to become the Indians’ first coach, albeit unpaid. Disciplinarian W. G. Thompson was put in charge of the football team in 1893 when Superintendent Pratt relented and allowed the boys to play against other schools but he was not a coach.

Pratt recalled McCormick’s exuberance in his memoir:

He was on the field one day taking part in instructing the boys how to fall on the ball when chasing it down the field. The ground was moist from recent rain, but he disregarded that and was giving them most enthusiastic incentive. The boys failed to execute the movement properly as he explained, and to show them how, without removing his hat or coat he rushed after and fell on the ball, as the game required. When he got up, his hat and clothing were some admonition against too sudden enthusiasm. The boys gave themselves up to the severest practice, and such energy they soon met all conditions.

Unfortunately, Vance wasn’t a full-time coach and, thus, couldn’t devote the time and energy necessary to lead the Indians to victory against the level of competition they played. He again helped in 1895 but couldn’t devote much time to what could best be called a hobby. He would be followed by other Yale men until 1899.

Tags:1892 Spalding's Guide, Nancy Luckenbaugh, Richard Henry Pratt, Vance McCormick, Walter Camp All America

Posted in Carlisle Indian School, Football | 1 Comment »

April 26, 2012

I thought I’d continue with the theme of Carlisle Indians who played football in WWI by looking through the 1919 Spalding Guide for references to the Carlisle team or its players. Before starting that, I checked to make sure that I hadn’t done it before as my memory isn’t as good as it once was. In January of this year, I did a piece about the Carlisle students whose names I wasn’t familiar with who were playing on military teams. I recollect having mentioned that, although the 1918 Spalding Guide included Carlisle’s schedule for that year, none of these games were played because the school was closed shortly before the beginning of the football season in 1918. Fortunately, some names I do recognize can be found in the 1919 book, too.

Om page 22 is the photograph of the 1918 Georgia Tech “Golden Tornado.” Joe Guyon is #8 and John Heisman is #12. Charles Guyon (Wahoo) isn’t in the photo. Perhaps, Heisman got rid of him by then. Page 188 displays headshots of players and coaches for the 1918 Mare Island Marines team. Lone Star Dietz, #3, coached this team composed mainly of his former Washington State players. So may of them were on this team that this photo was published as part of the Washington State yearbook for that year. The New Year’s Day game in Pasadena on January 1, 1919 was the second one for those who had also been on the 1915 Washington State squad that had played in Pasadena in 1916.

Page 263 includes a write up for the Base Section No. 5 team from Brest, a major port of embarkation: “On January 19, 1919, a Base foot ball squad was organized under Lieut. W. C. Collyer, former Cornell half-back. This squad was composed of the above mentioned engineers, together with several stars gathered together from different outfits. Of these, the most prominent was Artichoke, a former Haskell and Carlisle Indian star.” Not being aware of anyone named Artichoke, I am confident that the player in question was Chauncey Archiquette, Jim Thorpe’s early idol. Unfortunately, a team photo wasn’t included to see that Artichoke was indeed Archiquette.

Tags:Artichoke, Base Section 5, Brest, Golden Tornado, John Heisman, Mare Island Marines, Rose Bowl

Posted in Carlisle Indian School, Charles Guyon, Chauncey Archiquette, Football, Haskell Institute, Joe Guyon, Lone Star Dietz, Washington State University | Leave a Comment »